Fall 2021 Newsletter

Our first newsletter!

Welcome to the first newsletter of the Barnard Social Interaction Lab! Here, you will find exciting news about our student researchers, recent publications and presentations, and other lab events. I’ll post once at the beginning of every semester.

Summer in the Lab

We had a busy summer in the lab! Our three student researchers all did amazing work. Bri Vigorito joined the lab through the Barnard Summer Research Institute, and Talia Rosen and Zoe Zeltner conducted independent studies. Their primary project was running a study on Zoom about how people solve problems together. This was the lab’s first social interaction study that we conducted online, given the pandemic, and Bri did a great job setting up the whole study at the beginning of the summer. Talia and Zoe joined in late June, and everyone made fantastic progress on the study, working together to recruit participants and run study sessions. Data collection is still underway so stay tuned for results in a future newsletter.

Check out two awesome videos Bri made this summer, one showing a “day in the life” as a student researcher in our lab and another about her presentation for SRI. I used TikTok for the first time ever to access these so thanks for keeping me young, Bri!

As part of her work for the Admissions Office, Bri also wrote a post about finding research opportunities at Barnard and what it’s like to conduct research here. Thank you, Bri, for publicizing our work!

Recent Publications

Every newsletter, I’ll plan to give brief summaries of new publications from the lab. Of course, there are many more details relevant to the research than what I’m going to post here. I encourage you to read the full papers if you’re interested and to email me if you have more questions.

New Paper in Social Science and Medicine

Do doctors and patients exhibit similarity in their physiological responses during interactions with one another? Some of our new research, now published in Social Science and Medicine, suggests that they do. In this research, we measured the autonomic nervous system (ANS) responses of oncologists and patients during their consultations with each other. Specifically, we measured cardiac interbeat intervals—the amount of time in between successive heartbeats. Doctors and patients were matched for consultations based on which doctor was available in the hospital at the time of the patient’s appointment. Sometimes the consultation we measured was the first time a particular doctor and patient were meeting; other times, doctors and patients had already had several consultations together.

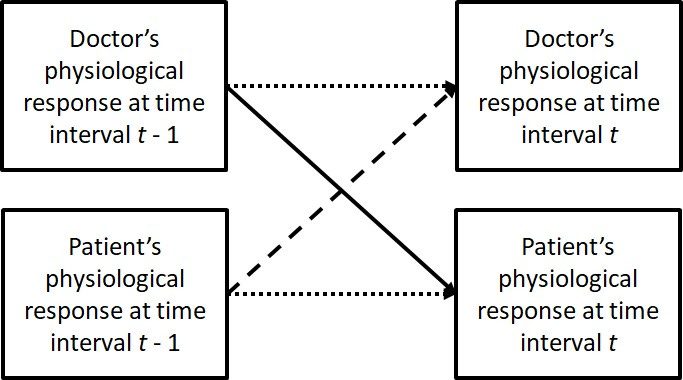

We examined whether there was physiological linkage of ANS responses between doctors and patients during their consultations. Here, linkage is the extent to which the physiological response of one person—the “sender”—at one time interval predicts the physiological response of the other person—the “receiver”—at a following time interval.

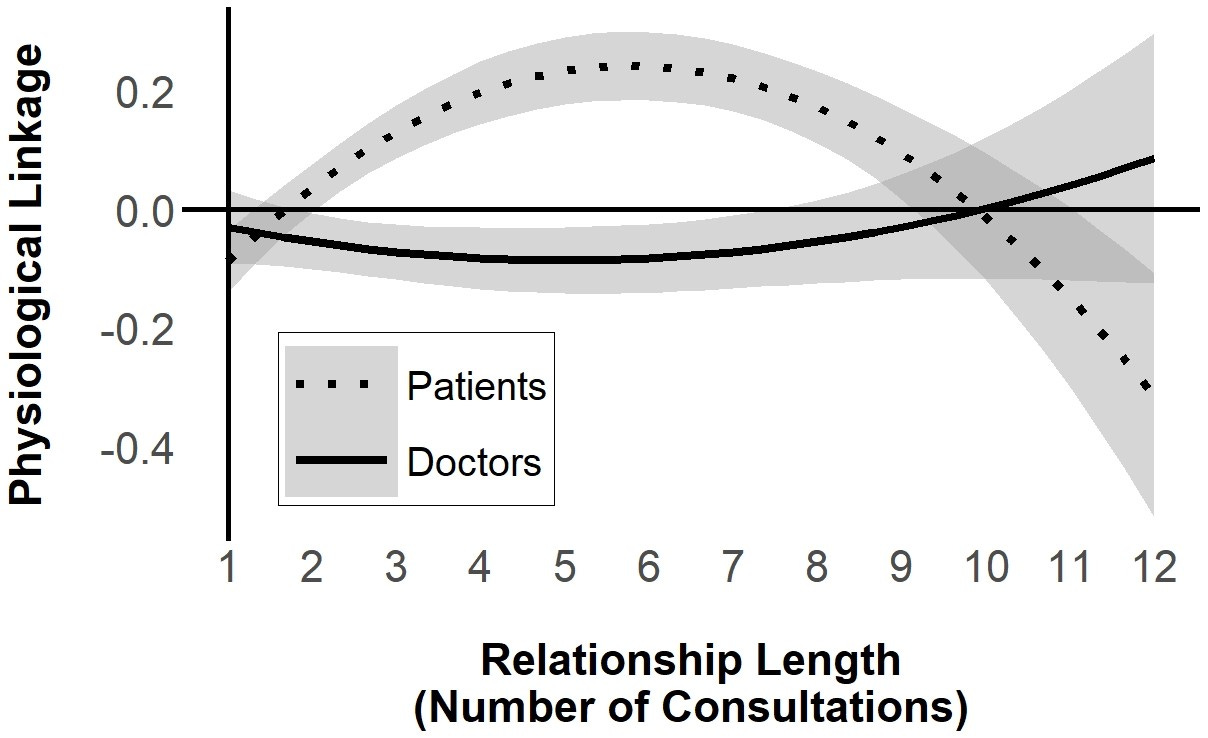

We found that patients showed physiological linkage to their doctors—meaning that doctors’ physiological responses positively predicted patients’ responses at a subsequent time interval—when their relationships spanned three to eight consultations. Patients were not linked to their doctors in shorter or longer relationships. Doctors were never significantly linked to their patients, meaning that patients’ physiological responses never predicted doctors’ responses.

Why does this happen? We don't know exactly. One idea is that these patterns arise because cancer patients are particularly attentive to oncologists they have known for at least a couple of consultations. This idea is based on work tying physiological linkage to psychosocial processes involving attention to others. Whatever the mechanism is, these results make an important step in understanding the kinds of effects that doctors have on patients. By "influencing" patients’ physiological responses on a moment-to-moment basis, this work shows that doctors may have even more influence over patients’ physiology than previously known.

Thank you to our student researchers, Posey Cohen and Talia Rosen, for helping me get this paper ready for publication and presentation! Thank you also to the many doctors and patients who participated in this study and to all the coauthors on this paper. You can read the full paper here.

New Paper in Psychoneuroendocrinology

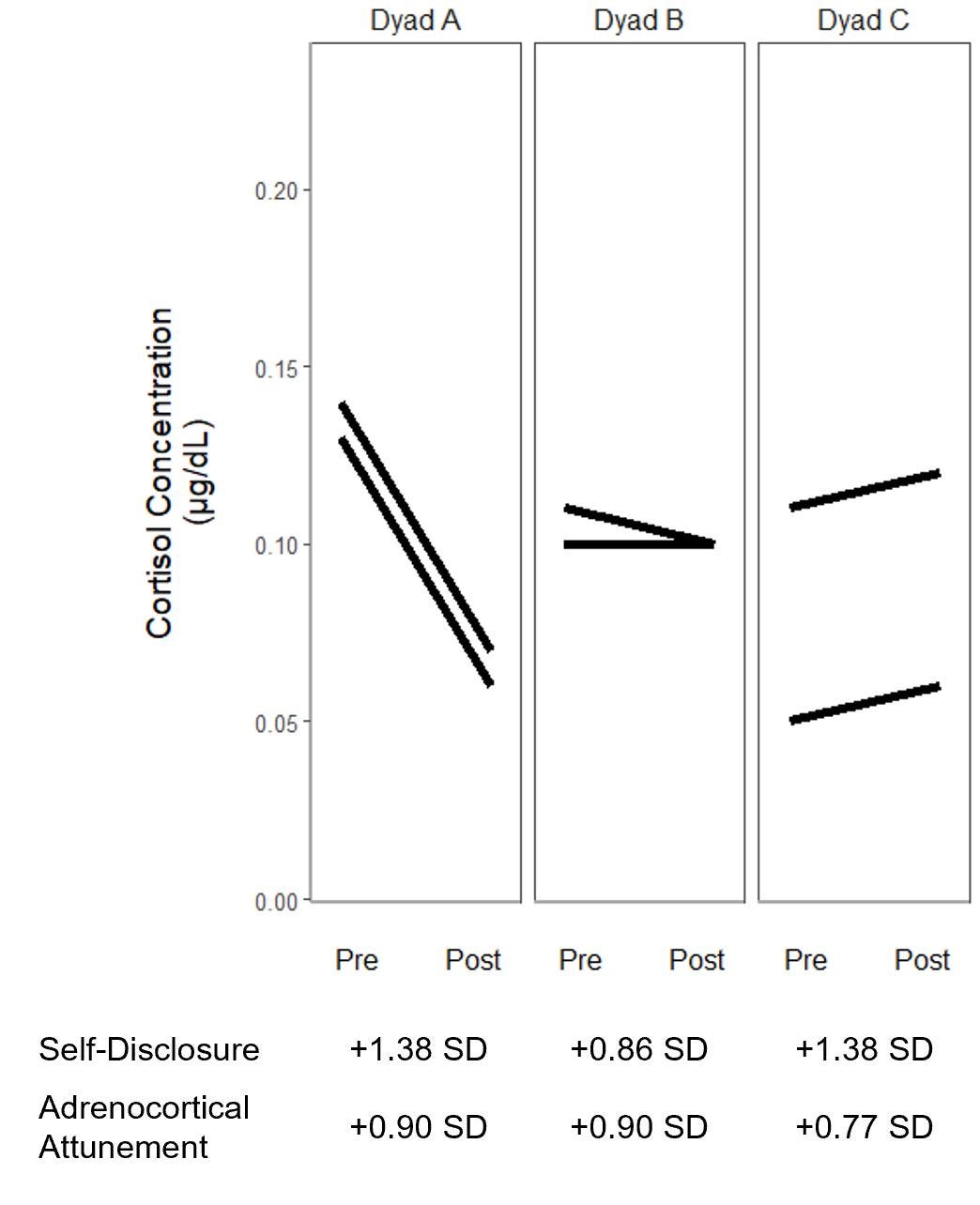

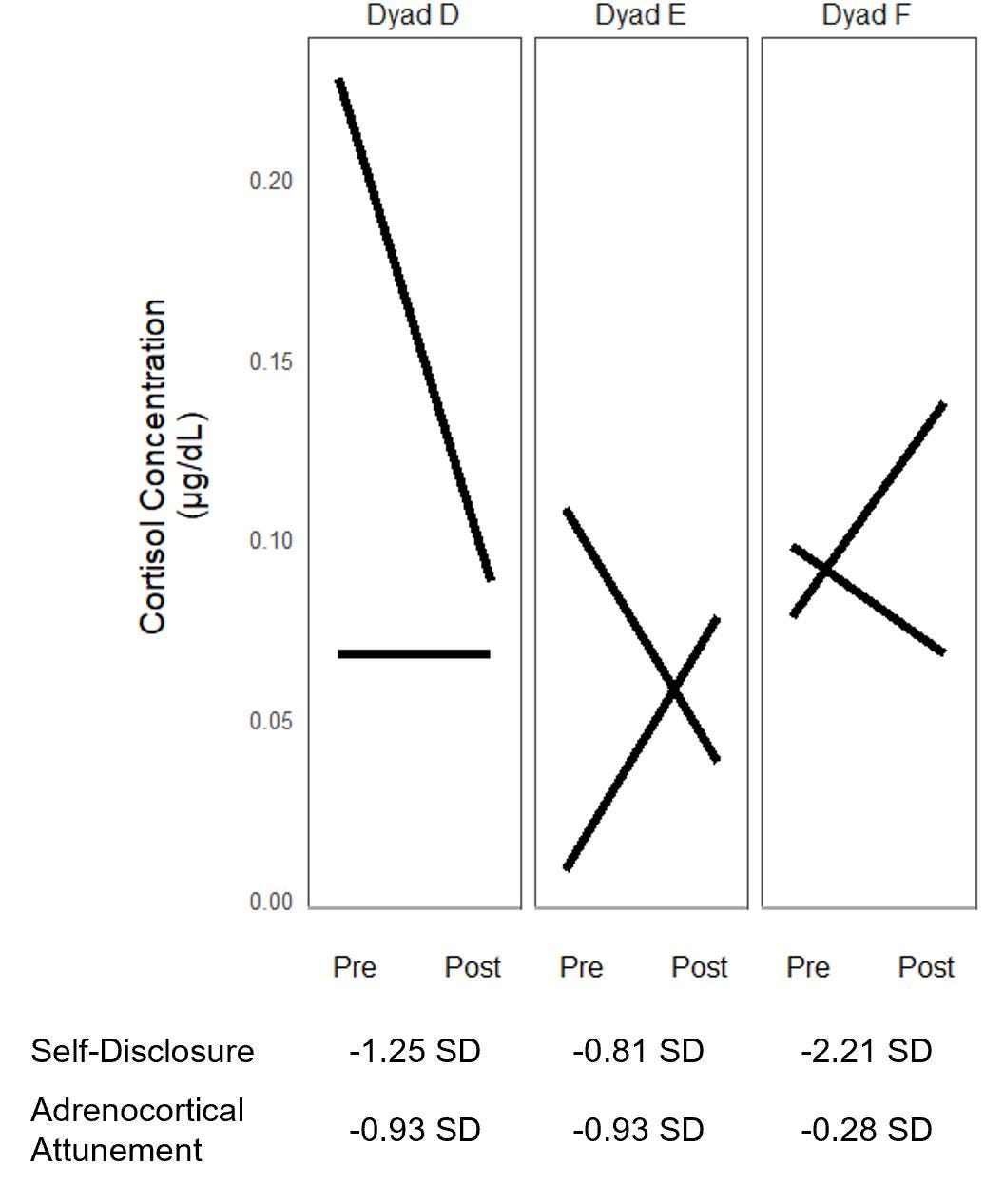

Does revealing more about oneself during a conversation with a new acquaintance predict greater similarity in cortisol changes with that person? Our new research in Psychoneuroendocrinology suggests that it does. In this research, pairs of new acquaintances asked each other personal questions. We measured self-disclosure—how much people revealed personal information to one another—while they were talking, and we also measured people's cortisol responses before and after the conversations. We found that self-disclosure was associated with more similarity in cortisol reactivity from before to after the conversation between dyad members, known as “adrenocortical attunement”.

For example, the figure below shows three example pairs in our study. These pairs all disclosed a relatively high amount of information to each other. As you can see, each pair also experienced similar changes in cortisol from before to after the conversation.

On the other hand, these three pairs disclosed a relatively low amount of information to each other. These dyads, however, did not experience similar changes in cortisol over the course of their conversations.

This research demonstrates one social process associated with adrenocortical attunement that occurs during early relationship formation and, in doing so, reveals a new process through which our physiological functioning may become tied to those around us—even those we have just met.

Many thanks to our co-authors on this project and to our student researcher, Nia Simmons, for helping me prepare this manuscript! For more details on this work, see the paper here.

That’s all for now! Thank you for reading, and I hope you all have a productive and fulfilling fall semester!